Subscribe to my feed for ingredients

Subscribe to my feed for ingredients  Add to My Yahoo

Add to My Yahoo

© Copyright 1995-2023, Clay Irving <clay@panix.com>, Manhattan Beach, CA USA

Subscribe to my feed for ingredients

Subscribe to my feed for ingredients  Add to My Yahoo

Add to My Yahoo

Egg Characteristics

Because birds preceded man in the evolutionary chain, both eggs and birds have been around longer than historians. Nobody really knows when the first fowl was domesticated, although Indian history places the date as early as 3200 B.C. Egyptian and Chinese records show that fowl were laying eggs for man in 1400 B.C. The dependability of the rooster's early morning call and the regularity with which newly laid eggs appeared probably inspired the Chinese to describe fowl as "the domestic animal who knows time."

|

|

The term "egg" means the shell egg of the domesticated chicken, turkey, duck, goose, or guinea. [1] It takes a hen 24 to 26 hours to produce an egg, then, 30 minutes later, the process starts again. About 240 million laying hens produce approximately 5.5 billion dozen eggs per year in the United States.

Nutritional Value of an Egg

| Egg contains the highest quality food protein known. It is so nearly perfect, in fact, that egg protein is often the standard by which all other proteins are judged. Based on the essential amino acids it provides, egg protein is second only to mother's milk for human nutrition. On a scale with 100 representing top efficiency, these are the biological values of proteins in several foods.

Eggs are packed with a number of nutrients. One egg has 13 essential vitamins and minerals for only 75 calories. Eggs are also a good source of high-quality protein including all nine essential amino acids, as well as healthy unsaturated fats. Lutein and zeaxanthin, two antioxidants that contribute to eye health, are also found in eggs.

|

|

Cholesterol - One Large egg contains 213 mg cholesterol. Cholesterol is a fat-like substance found in every living cell in the body. It is made in necessary amounts by the body and is stored in the body. It is especially concentrated in the liver, kidney, adrenal glands and the brain. Cholesterol is required for the structure of cell walls, must be available for the body to produce vitamin D, is essential to the production of digestive juices, insulates nerve fibers and is the basic building block for many hormones. In other words, cholesterol is essential for life.

Your body produces all the cholesterol it needs. Most of the cholesterol found in the blood and tissues come from this internal synthesis. However, dietary excesses—too many calories, too much fat and saturated fat and high intakes of cholesterol—may increase the level in the blood. Saturated fat has the greatest influence on raising blood cholesterol.

Dietary cholesterol, found in all foods from animals, does not automatically raise blood cholesterol levels. Generally the body compensates for dietary cholesterol by synthesizing smaller amounts in the liver, by excreting more or by absorbing less.

Elevated blood cholesterol does increase the risk of heart disease. You should know your blood cholesterol level and follow your doctor's advice if it is elevated. In a blood cholesterol-lowering diet, cutting down on fat and saturated fat is the most important change you can make. Although egg yolks are usually restricted, it is rarely necessary to avoid them completely, and egg whites can be used freely.

Despite rumors to the contrary, eggs laid by Aracauna fowl, eggs laid by free-running hens and fertilized eggs do not contain less cholesterol than regular supermarket eggs. Cooking does not affect the cholesterol content of eggs.

Lecithin - One of the factors in egg yolk that helps to stabilize emulsions such as mayonnaise, salad dressings and Hollandaise sauce. Lecithin contains a phospholipid, acetycholine, which has been demonstrated to have a profound effect on brain function.

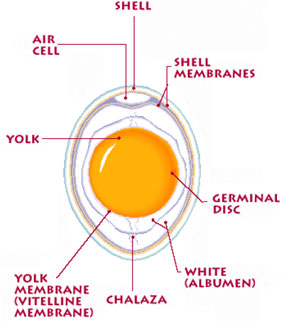

Anatomy of an Egg

| Shell - Although the shell acts as a protective barrier for the inside of the egg, it is still very porous with approximately 17,000 pores through which air flows. The shell is largely composed of calcium carbonate (about 94%) with small amounts of magnesium carbonate, calcium phosphate and other organic matter including protein. Shell strength is greatly influenced by the minerals and vitamins in the hen's diet, particularly calcium, phosphorus, manganese and Vitamin D. If the diet is deficient in calcium, for instance, the hen will produce a thin or soft-shelled egg or possibly an egg with no shell at all. Occasionally an egg may be prematurely expelled from the uterus due to injury or excitement. In this case, the shell has not had time to be completely formed. Shell thickness is also related to egg size which, in turn, is related to the hen's age. As the hen ages, egg size increases. The same amount of shell material which covers a smaller egg must be "stretched" to cover a larger one, hence the shell is thinner. Shell Membranes - There are two membranes on the inside of the shell. One membrane sticks to the shell and one surrounds the white (albumen). The second line of defense against bacteria. They are composed of thin layers of protein. Germinal Disk - The entrance of the latebra, the channel leading to the center of the yolk. A slight depression on the surface of the yolk, the entry for the fertilization of the egg. When the egg is fertilized, sperm enter by way of the germinal disc, travel into a tube-like thread called the "neck of latebra" to the center to the embryonic disc, a 2 to 3mm diameter structure in the nucleus of pander. Subsequently, a chick embryo starts to form. White (Albumen) - There are two layers: thin and thick albumen. Mostly made of water, high quality protein and some minerals. Represents ⅔ of the egg's weight (without the shell). When a fresh egg is broken, the thick albumen stands up firmly around the yolk. Chalazae - Pronounced "kuh-LAY-zee", it is a pair of spiral white strands attached to two sides of the yolk and anchor it to the shell. The fresher the egg, the more prominent the chalazee. Yolk Membrane (Vitelline Membrane) - Surrounds and holds the yolk. The fresher the egg, the stronger the membrane. Yolk - The egg's major source of vitamins and minerals, including protein and essential fatty acids. Represents ⅓ of the egg's weight (without the shell). Yolk colors range from light yello to deep orange, depending on the chicken's diet. Air Cell - Forms at the wide end of the egg as it cools after being laid. The fresher the egg, the smaller the air cell. |

Blood Spots - Also called meat spots. Occasionally found on an egg yolk. Contrary to popular opinion, these tiny spots do not indicate a fertilized egg. Rather, they are caused by the rupture of a blood vessel on the yolk surface during formation of the egg or by a similar accident in the wall of the oviduct. Less than 1% of all eggs produced have blood spots.

Mass candling methods reveal most eggs with blood spots and those eggs are removed but, even with electronic spotters, it is impossible to catch all of them. As an egg ages, the yolk takes up water from the albumen to dilute the blood spot so, in actuality, a blood spot indicates that the egg is fresh. Both chemically and nutritionally, these eggs are fit to eat. The spot can be removed with the tip of a knife, if you wish.

Double-Yolked Eggs - Often produced by young hens whose egg production cycles are not yet completely synchronized. They're often produced, too, by hens who are old enough to produce Extra Large eggs. Genetics is a factor, also. Occasionally a hen will produce double-yolked eggs throughout her egg-laying career. It is rare, but not unusual, for a young hen to produce an egg with no yolk at all.

Grades

Classification determined by the interior and exterior quality of the egg at the time it is packed. In some egg-packing plants, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) provides a grading service for shell eggs. The official USDA grade shield on an egg carton certifies that the eggs have been processed, packaged and certified under federal supervision according to the U.S. Standards, Grades and Weight Classes for Shell Eggs established by USDA. Plant processing equipment, facilities, sanitation and operating procedures are continuously monitored by the USDA grader.

Although the USDA grading service is not mandatory, the U.S. Standards have been incorporated into state egg laws and the regulations affecting the marketing of eggs. All states have laws regulating the sales of eggs that must comply with the U.S. Standards; however, some states impose additional requirements.

Some egg packers follow state standards, which must meet or exceed USDA standards. Some states have state seal programs which indicate that the eggs are produced within the state and are subject to continuing state quality checks.

In the grading process, eggs are examined for both interior and exterior quality before they're sorted according to weight (size). Grade quality and size are not related to one another. In descending order of quality, grades are designated AA, A and B.

| Eggs are graded by their internal characteristics, not by how they taste or react when cooking. Grades AA and A, the most common, have tall yolks and thick whites that don't spread much. Grade A whites are not as thick as Grade AA whites. Grade B eggs—Often used in food service—have flatter yolks and thinner whites than Grades A and AA. |  Grade AA |

Grade A |

Grade B |

Albumen is judged on the basis of clarity and firmness or thickness. A clear albumen is free from discolorations or from any floating foreign bodies.

Factors determining yolk quality are distinctness of outline, size and shape and absence of such defects as blemishes or mottling, germ development or blood spots.

Higher-grade eggs have shallower air cells. In Grade-AA eggs, the air cell may not exceed 1/8 inch in depth and is about the size of a dime. Grade-A eggs may have air cells over 3/16 inch in depth. There is no limit on air cell size for Grade-B eggs. While air-cell size is considered in grading and eggs take in air as they age, the size of the air cell does not necessarily relate to freshness because size varies from the moment contraction occurs after laying. To judge freshness, use carton dates.

Examination of the interior of the egg to determine the grade is done by candling or by the breakout method using the Haugh unit system to evaluate the albumen, yolk and air cell.

|

Candling Method - When an egg is rotated over the candling light, its yolk swings toward the shell. The distinctness of the yolk outline depends on how close to the shell the yolk moves, which is influenced by the thickness of the surrounding albumen. Thick albumen permits limited yolk movement while thin albumen permits greater movement—the less movement, the thicker the white and the higher the grade.

During candling each egg rotates over a strong light source which enables the operator to see inside the egg and look for any internal defects as well as shell defects. There is a button next to each egg. If a defect is found in the egg, such as a blood spot or a hairline crack in the shell, the operator presses a button next to the egg. This button is linked to an electronic sensor in the machine which makes sure that this egg is not sent to the First Quality packing shutes. |

| Breakout Method Using Haugh Unit System - Sample eggs selected at random are broken out onto a level surface and the height of the thick albumen is measured with a micrometer. This measurement, referred to as "HU", is then correlated with the weight of the egg to give a Haugh unit measurement. A high Haugh value means high egg quality. At the same time, the condition of the yolk is observed.

To make a Haugh unit measurement of an egg, it is brought within a specified temperature range, weighed, and broken onto a flat plate. A tripod micrometer is then used to measure the height of the albumen midway between the yolk and the edge of the albumen. A comparison of this height with the weight of the egg yields a whole-number score, typically between 20 and 100, or somewhat more. (Slide rules for making the comparison are commercially available, and the comparison may be built into the scale of the micrometer.) Scores of 90 HU and above are considered excellent, 70 HU is acceptable, and buyers generally reject eggs that score below 60 HU. In United States egg grades, AA grade eggs score 72 HU or higher, A grade, 60 to 72 HU, and B grade, lower than 60 HU (all measured at a temperature between 45°F and 60°F) |

|

| AA Quality | A Quality | B Quality |

| The shell must be clean, unbroken, and practically normal. The air cell must not exceed 1/8 inch in depth, may show unlimited movement, and may be free or bubbly. The white must be clear and firm so that the yolk is only slightly defined when the egg is twirled before the candling light. The yolk must be practically free from apparent defects. [2] | The shell must be clean, unbroken, and practically normal. The air cell must not exceed 3/16 inch in depth, may show unlimited movement, and may be free or bubbly. The white must be clear and at least reasonably firm so that the yolk outline is only fairly well defined when the egg is twirled before the candling light. The yolk must be practically free from apparent defects. [3] | The shell must be unbroken, may be abnormal, and may have slightly stained areas. Moderately stained areas are permitted if they do not cover more than 1/32 of the shell surface if localized, or 1/16 of the shell surface if scattered. Eggs having shells with prominent stains or adhering dirt are not permitted. The air cell may be over 3/16 inch in depth, may show unlimited movement, and may be free or bubbly. The white may be weak and watery so that the yolk outline is plainly visible when the egg is twirled before the candling light. The yolk may appear dark, enlarged, and flattened, and may show clearly visible germ development but no blood due to such development. It may show other serious defects that do not render the egg inedible. Small blood spots or meat spots (aggregating not more than 1/8 inch in diameter) may be present. [4] |

All ungraded eggs must meet a B grade. "Restricted eggs" do not meet B grade standards and a generally prevented from reaching the consumer. Two types of restricted eggs, "checks" (the shell is broken or cracked, but the membrane is intact) and "dirties" (the shell is unbroken and has adhering dirt or foreign material, prominent stains or moderate stains), may be sold to be processed in factories.

Size

Eggs come is a variety of sizes. Younger hens produce smaller eggs, which are often regarded as better quality than larger eggs. Medium eggs are best for breakfast cookery. Large and extra-large eggs are generally used for cooking and baking, where the whole egg's appearance is less critical. [5]

| U.S. sizes are defined by the weight of a dozen eggs—Not individual eggs. An egg in a carton of Extra Large eggs need not weigh at least 2¼ ounces (27 ounces divided by 12), but the entire dozen must weigh at least 27 ounces.

Most recipes with eggs as an ingredient usually mean large eggs. If using 3 or less eggs, the extra large, large and medium sizes are interchangeable. If using 4 or more eggs, use this conversion:

|

|

Color

| The color comes from pigments in the outer layer of the shell and may range in various breeds from white to deep brown. The breed of hen determines the color of the shell. Breeds with white feathers and ear lobes lay white eggs; breeds with red feathers and ear lobes lay brown eggs. White eggs are most in demand among American buyers. In some parts of the country, however, particularly in New England, brown shells are preferred. The Rhode Island Red, New Hampshire and Plymouth Rock are breeds that lay brown eggs. Since brown-egg layers are slightly larger birds and require more food, brown eggs are usually more expensive than white. |  |

| Photograph by Clay Irving, Roadside produce stand in Pattaya Thailand |

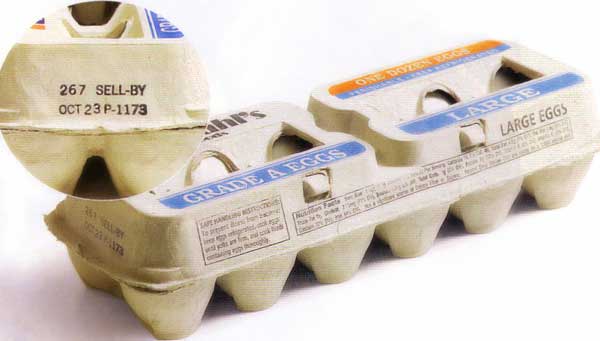

Freshness

Check the expiration date. The "rule of thumb" is that you can safely eat an egg up to two weeks past expiration. The date the eggs were packed is often indicated on the carton by a number from 1 to 365, representing consecutive days of the year (this is a Julian date). The carton below was packed on day 267—September 24. If properly refigerated, eggs are good 4 to 5 weeks beyond the packaged date, indicated by the "SELL-BY" or expiration date also on the carton.

|

| Photograph from CuisineAtHome, Issue 68, April 2008 |

To check your egg without cracking it open, fill a bowl with water. Place your eggs in the water and see if they sink or float. Generally, the safe ones will sink to the bottom and rest on their sides. The bad ones will stand up and they might float because the air cell has enlarged sufficiently to make the egg bouyant—As the egg ages, moisture and carbon dioxide leave through the pores of the shell, air enters to replace them and the air cell becomes larger.

Crack the egg into a bowl and watch the consistency of the egg white. The runnier the egg is, the more cautious you should be about using it. The egg is fresh if it has a perky yolk, thick whites, and a thick chalazae. Older eggs have flatter yolks and runnier whites.

Storage

The most familiar egg package is the pulp or foam carton holding 12 eggs. There are sizes other than dozens available in some regions such as 2½ or 3 dozen small eggs per package or packs of 6, 8 or 18. The sponginess of the carton insulates the eggs from jolts. New package designs are constantly being tested to provide the best protection for the eggs.

|

Whether foam or pulp, the carton prevents loss of moisture and carbon dioxide and also keeps the eggs from picking up undesirable odors and flavors. Even though your refrigerator may have an egg shelf in the door, it is better to store eggs in the carton on an inside shelf for freshness' sake.

Eggs are placed in their cartons large end up to keep the air cell in place and the yolk centered. Eggs should be stored in the refrigerator—Eggs age more in 1 day at room temperature than they will in 1 week in the refrigerator. Hard-cooked eggs should be cooled and refrigerated in their shells in their cartons and used within 1 week. When storing hard-cooked eggs, you may notice a "gassy" odor in your refrigerator. It may be more noticeable when the refrigerator is opened infrequently. The odor is caused by hydrogen sulfide which forms when the eggs are cooked, is harmless and usually dissipates within a few hours. |  Photograph by Clay Irving, Torrance Farmer's Market |

For outdoor eating occasions, eggs can be kept refrigerator-cold with ice or commercial coolant in an insulated bag or picnic cooler as long as the ice lasts or the coolant remains almost at freezing. Unless it's quite cold weather, for hiking, backpacking, camping and boating when refrigeration or cooler facilities aren't available, it's better to use dried eggs. Usually available in sporting goods stores, dried eggs can be reconstituted with purified water and used in most of the ways you would use fresh eggs. Specially coated hard-cooked eggs which keep without refrigeration for a considerable length of time are also available in some areas. Pickling and other forms of preservation are additional possibilities.

If a recipe calls for only whites or only yolks, refrigerate the leftover whites in a covered container up to 4 days. Store yolks in water in a covered container in the refrigerator and use in a day or two. If you can't use the yolks quickly enough, hard cook them. Carefully place them in a single layer in a saucepan and add enough water to come at least 1 inch above the yolks. Cover and quickly bring just to boiling. Remove from heat and let stand, covered, in the hot water for about 15 minutes. Remove with a slotted spoon and store in a tightly sealed container in the refrigerator up to 4 or 5 days.

Freezing Eggs - Eggs can be frozen using these techniques:

| Whites | Break and separate the eggs, one at a time, making sure that no yolk gets in the whites. Pour them into freezer containers, seal tightly, label with the number of egg whites and the date, and freeze. For faster thawing and easier measuring, first freeze each white in an ice cube tray and then transfer to a freezer container. |

| Yolks | Egg yolks require special treatment. The gelation property of yolk causes it to thicken or gel when frozen. If frozen as is, egg yolk will eventually become so gelatinous it will be almost impossible to use in a recipe. To help retard this gelation, beat in either 1/8 teaspoon salt or 1½ teaspoons sugar or corn syrup per ¼ cup egg yolks (4 yolks). Label the container with the number or yolks, the date, and whether you've added salt (for main dishes) or sweetener (for baking or desserts). |

| Whole eggs | Beat just until blended, pour into freezer containers, seal tightly, label with the number of eggs and the date, and freeze. |

| Hard-cooked | Hard-cooked yolks can be frozen to use later for toppings or garnishes. Carefully place the yolks in a single layer in a saucepan and add enough water to come at least 1 inch above the yolks. Cover and quickly bring just to boiling. Remove from the heat and let stand, covered, in the hot water about 15 minutes. Remove with a slotted spoon, drain well and package for freezing. Hard-cooked whole eggs and whites become tough and watery when frozen, so don't freeze them. |

To use frozen eggs, thaw frozen eggs overnight in the refrigerator or under running cold water. Use yolks or whole eggs as soon as they're thawed. Once thawed, whites will beat to better volume if allowed to sit at room temperature for about 30 minutes.

Cooking with Eggs

Certain terms or phrases occur with regularity in egg recipes. Here are many of them along with an explanation. [6]

| Cook until knife inserted near center comes out clean | Baked custard mixtures are done when a metal knife inserted off center comes out clean. The very center still may not be quite done, but the heat retained in the mixture will continue to cook it after removal from the oven. Cooking longer may result in a curdled and/or weeping custard. Cooking a shorter period may result in a thickened but not set custard. |

| Cook until just coats a metal spoon | For stirred custard mixtures, the eggs are cooked to the proper doneness when a thin film adheres to a metal spoon dipped into the custard. This point of coating a metal spoon is 20 to 30 degrees below boiling. Stirred custards should not boil. The finished product should be soft and thickened but not set. Stirred custards will thicken slightly after refrigeration. |

| Slightly beaten | Use a fork or whisk to beat eggs just until the yolks and whites are blended. |

| Well beaten | Use a mixer, blender, beater or whisk to beat eggs until they are light, frothy and evenly colored. |

| Thick and lemon-colored | Beat yolks at high speed with an electric mixer until they become a pastel yellow and form ribbons when the beater is lifted or they are dropped from a spoon, about 3 to 5 minutes. Although yolks can't incorporate as much air as whites, this beating does create a foam and is important to airy concoctions such as sponge cakes. |

| Add a small amount of hot mixture to eggs/egg yolks | When eggs or egg yolks are added to a hot mixture all at once, they may begin to coagulate too rapidly and form lumps. So, stir a small amount of the hot mixture into the yolks to warm them and then stir the warmed egg yolk mixture into the remaining hot mixture. This is called tempering. |

| Room temperature | Some recipes call for eggs to be at room temperature before eggs are to be combined with a fat and sugar. Cold eggs could harden the fat in such a recipe and the batter might become curdled. This could affect the texture of the finished product. Remove eggs from the refrigerator about 30 minutes before using them or put them in a bowl of warm water while assembling other ingredients. For all other recipes, however, use eggs straight from the refrigerator. |

| Separated |

Fat inhibits the foaming of egg whites. Since egg yolks contain fat, they are often separated from the whites and the whites beaten separately to allow them to reach their fullest possible volume. Eggs are easiest to separate when cold, but whites reach their fullest volume if allowed to stand at room temperature for about 30 minutes before beating.

Many inexpensive egg separators are available. To separate, tap the midpoint of the egg sharply against a hard surface. Holding the egg over the bowl in which you want the whites, pull the halves apart gently. Let the yolk nestle into the cup like center of the separator and the white will drop through the slots into the bowl beneath. Drop 1 egg white at a time into a cup or small bowl and then transfer it to the mixing bowl before separating another egg. This avoids the possibility of yolk from the last egg getting into several whites. Drop the yolk into another mixing bowl if needed in the recipe or into a storage container if not. |

| Add cream of tartar | Egg whites beat to greater volume than most other foods including whipping cream, but the air beaten into them can be lost quite easily. A stabilizing agent such as cream of tartar is added to the whites to make the foam more stable. Lemon juice works much the same way. |

| Add sugar, 1 to 2 tablespoons at a time | When making meringues and some cakes, sugar is slowly added to beaten egg whites. This serves to increase the stability of the foam. Sugar, however, can retard the foaming of the whites and must be added slowly so as not to decrease the volume. Beat the whites until foamy, then slowly beat in the sugar. |

| Stiff but not dry | Beat whites with a mixer, beater or whisk just until they no longer slip when the bowl is tilted. (A blender or food processor will not aerate them properly.) If egg whites are under beaten, the finished product may be heavier and less puffy than desired. If egg whites are over beaten, they may form clumps which are difficult to blend into other foods in the mixture and the finished product may lack volume. |

| Stiff peaks form | See Stiff but not dry. |

| Soft peaks or piles softly | Whites that have been beaten until high in volume but not beaten to the stiff peak stage. When beater is lifted, peaks will form and curl over slightly. |

| Gently folded | When combining beaten egg whites with other heavier mixtures, handle carefully so that the air beaten into the whites is not lost. It's best to pour the heavier mixture onto the beaten egg whites. Then gradually combine the ingredients with a downward stroke into the bowl, across, up and over the mixture motion, using a spoon or rubber spatula. Come up through the center of the mixture about every three strokes and rotate the bowl as you are folding. Fold just until there are no streaks remaining in the mixture. Don't stir because this will force air out of the egg whites. If you have a stand mixer, put the mixing bowl on the turntable for easier turning as you fold. |

| Curdling |

Also known as syneresis or weeping. When egg mixtures such as custards or sauces are cooked too rapidly, the protein becomes overcoagulated and separates from the liquid leaving a mixture resembling fine curds and whey. If curdling has not progressed too far, it may sometimes be reversed by removing the mixture from the heat and stirring or beating vigorously.

To prevent syneresis or curdling, use a low temperature, stir, if appropriate for the recipe, and cool quickly by setting the pan in a bowl of ice or cold water and stirring for a few minutes. The term curdling is usually used in connection with a stirred mixture such as custard sauce, while weeping or syneresis are more often used with reference to pie meringues or baked custards. |

Peeling a Hard-Cooked Egg

Here is a neat trick to quickly peel a hard-cooked egg.

How to Tell a Raw Egg from a Hard-Cooked Egg

If you hold up two eggs and one is hard-boiled and the other is raw, you might wonder how to know which is which. A simple test will reveal the answer. Spin them carefully on a countertop. The hard-boiled one spins and the raw one doesn't. This is because the hard-boiled egg is solid so everything spins in one direction, while the inside of the raw egg sloshes in different directions and, therefore, doesn't allow it to spin. Try it and see for yourself.

Sometimes Cooked Eggs Turn Green

Sometimes a large batch of scrambled eggs may turn green. Although not pretty, the color change is harmless. It is due to a chemical change brought on by heat and occurs when eggs are cooked at too high a temperature, held for too long, or both. Using stainless steel equipment and low cooking temperature, cooking in small batches, and serving as soon as possible after cooking will help to prevent this. If it is necessary to hold scrambled eggs for a short time before serving, it helps to avoid direct heat. Place a pan of hot water between the pan of eggs and the heat source.

Varieties

|

|

|

|

| Quail Egg | Duck Egg | Chicken Egg | Goose Egg |

Reng Khai (Nest Eggs) รังไข [Thailand]

In Thailand, unlaid, immature eggs are harvested from hens when they are butchered. They are used like regular eggs, in soup, for example.

Photograph by Clay Irving, Market in Pattaya, Thailand

Balut (Fertilized Duck Eggs) [Philipines]

A balut is a fertilized duck (or chicken) egg with a nearly-developed embryo inside that is boiled and eaten in the shell. They are common, everyday food in some countries in Asia, such as in the Philippines, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

Balut are most often eaten with a pinch of salt, though some balut-eaters prefer chili and vinegar to complement their egg. The eggs are savored for their balance of textures and flavors; the broth surrounding the embryo is sipped from the egg before the shell is peeled and the yolk and young chick inside can be eaten. All of the contents of the egg are consumed, although the whites may remain uneaten. In the Philippines, balut have recently entered higher cuisine by being served as appetizers in restaurants: cooked adobo style, fried in omelettes or even used as filling in baked pastries.

Photograph by Angela in the Philipines

Fertilized duck eggs are kept warm in the sun and stored in baskets to retain warmth. After nine days, the eggs are held to a light to reveal the embryo inside. Approximately eight days later the balut are ready to be cooked, sold, and eaten. Vendors sell cooked balut out of buckets of sand, used to retain warmth, and are accompanied by small packets of salt.

Salted Duck Eggs [China]

Salted duck egg is a Chinese preserved food product made by soaking duck eggs in brine, or packing each egg in damp salted charcoal. In Asian supermarkets, these eggs are sometimes sold covered in a thick layer of salted charcoal paste. The eggs may also be sold with the salted paste removed, wrapped in plastic, and vacuum packed. From the salt curing process, the salted duck eggs have a briny aroma, a very liquid egg white and a yolk that is bright orange-red in colour, round, and firm in texture.

Photograph by Queenie, Phuket, Thailand

Salted duck egg is a Chinese preserved food product made by soaking duck eggs in brine, or packing each egg in damp salted charcoal. In Asian supermarkets, these eggs are sometimes sold covered in a thick layer of salted charcoal paste. The eggs may also be sold with the salted paste removed, wrapped in plastic, and vacuum packed. From the salt curing process, the salted duck eggs have a briny aroma, a very liquid egg white and a yolk that is bright orange-red in colour, round, and firm in texture.

Salted duck eggs are normally boiled or steamed before being peeled and eaten as a condiment to congee or cooked with other foods as a flavouring. The egg white has a sharp, salty taste. The orange red yolk is rich, fatty, and less salty. The yolk is prized and is used in Chinese mooncakes to symbolize the moon.

Despite its name, salted duck eggs can also be made from chicken eggs though the taste and texture will be somewhat different, and the egg yolk will be less rich.

Egg Production Methods

|

Battery Farming This is the mass production method by which most eggs are produced and against which most of the animal welfare organisations target their activities. The most intensive system is the laying cage with around four birds to a cage. There is a combination of natural and artificial light otherwise the birds would not lay throughout the winter. The buildings, often as big as football pitches can each hold up to 200,000 birds. Fresh feed and water are provided automatically and the sloping wire mesh floor allows the eggs to roll onto a collection belt. The system has its advantages as the environment is easy to control and the droppings fall through the mesh floor of the cage, minimising disease risks. |

|

|

Barn Production The halfway house between cage egg production and a free-range system is a barn or deep litter system. Birds can move around freely in a barn-like house and express natural behaviour. There are perches and dust-bathing facilities and they can escape aggression by moving around. Eggs are laid in individual or communal nest boxes. Again, there are no predators, lighting is controlled and feed and water provided automatically. A conveyor belt may take the eggs to a collection point. There is an increased risk of parasites and droppings must be managed. The birds will however still live in huge flocks sometimes over 10,000 in one barn and will never see the light of day. |

|

|

Free Range Housing for free-range birds is almost identical to the barn system. However, there are "pop holes" to allow the chickens to range freely in daylight—albeit in far larger flocks than in the wild. So that eggs remain affordable to the consumer, birds are kept in flocks of several thousand with about 400 birds to an acre. The hens can scratch and dust-bathe—they have a varied diet from foraging in pasture for weeds and worms. There is a greater disease risk owing to concentrations of droppings and contact with wild birds. Pastures must be rotated and predators such as foxes may be an issue. |

|

Organic Eggs

In October 2002, the National Organic Standard Board set national guidelines that must be met by producers wishing to market "organic" eggs.

Eggs from hens fed rations having ingredients that were grown without pesticides, fungicides, herbicides or commercial fertilizers. No commercial laying hen rations ever contain hormones. Due to higher production costs and lower volume per farm, organic eggs are more expensive than eggs from hens fed conventional feed. The nutrient content of eggs is not affected by whether or not the ration is organic.

Free Range Organic Eggs

These are eggs laid by free range hens, which are allowed to roam outdoors, and feed freely on a certified 100% organically grown wheat based diet. They are allowed to roam freely, but they are nevertheless contained in pens for their own safety. Pop holes are created to allow the hens access to the outside range. The feed contains no animal by-products or fishmeal and the yolks of organic eggs are paler due to the wheat-based diet. The hens do not move on soil, but chaff and shavings. This is for reasons of hygiene and to prevent disease.

Free Range Omega-3 Eggs

These are eggs that are laid by free range hens that are allowed to roam outdoors and feed on a vegetarian diet of grains and pulses enriched with omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin E. No fishmeal or animal by-products are used. All the other conditions affecting free range egg-laying hens remain pertinent.

Araucana Eggs

Araucana eggs are from Araucana chickens, native to South America. Nutritionally, these bluish-green eggs are not much different from traditional white and brown eggs you might find at the local grocery store. Actually, even though many consumers think these eggs are lower in cholesterol, eggs from this breed have a higher cholesterol content.

Lutein Eggs

Eggs from birds raised on a diet that includes marigold extract are high in lutein, a nutrient that has been shown to reduce the risk of macular degeneration (the leading cause of blindness in people 65 and older.) According to one study, lutein in eggs is better absorbed by the body than is lutein from other sources.

Pasteurized Eggs

Pasteurized shell eggs are a good choice for people who want to use raw eggs in recipes that do not require further cooking, such as homemade ice-cream or Caesar salad dressing. These eggs have been heat treated to kill potential salmonella bacteria found inside. (The risk of purchasing an egg contaminated with salmonella bacteria is one in 20,000 eggs.) However, due to the heat processing, these eggs may have slightly lower levels of heatsensitive vitamins.

Fertile Eggs

Some cultures consider fertile eggs a delicacy. But aside from coming from a hen that has possibly mated with a rooster, there is no nutritional difference between fertile eggs and generic eggs.

Footnotes

[1] U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Title 21 - Food and Drugs, Chapter 15 - Egg Products Inspection, §1033 - Definitions, (g) Egg

[2] USDA United States Standards, Grades, and Weight Classes for Shell Eggs, §56.201

[3] USDA United States Standards, Grades, and Weight Classes for Shell Eggs, §56.202

[4] USDA United States Standards, Grades, and Weight Classes for Shell Eggs, §56.203

[5] The Professional Chef, 8th Edition, The Culinary Institute of America

[6] From American Egg Board.