Architecture in Time

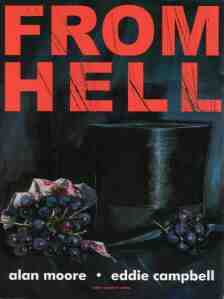

A Review of Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell's FROM HELL

by Bala Menon

Alan Moore, long known as one of comicdom's finest writers,

joins with Eddie Campbell to produce this tale of Jack the Ripper.

|

Here, Moore builds a tale that stretches in ripples across time,

as he attempts his own explanation of the Ripper murders.

Not a three-dimensional pattern across Whitechapel, but rather a

four-dimensional pattern across time, with the effects

(and causes) of the Ripper murders travelling across the

centuries, one man's plan to transcend his own mortality,

at once an act of personal worship as well as an attempt

to exalt himself and finally attain the face of God.

Focusing, not from the point of view of the hunters, but

of the Ripper himself, Moore analyzes the available information,

chooses whom he believes to be the most likely Ripper,

and projects the suspect's beliefs and motivations from what

is known of his life. The result is an appallingly dark story,

made even more horrific by the non-randomness, the callousness

of the killings.

Immensely erudite, a rationale is presented for the Ripper

murders. Not simply a hack-and-slash murderer, lashing out

mindlessly at any woman who crosses his path, but rather,

an intricate plan, aimed at specific targets, for a specific

purpose.

|

|

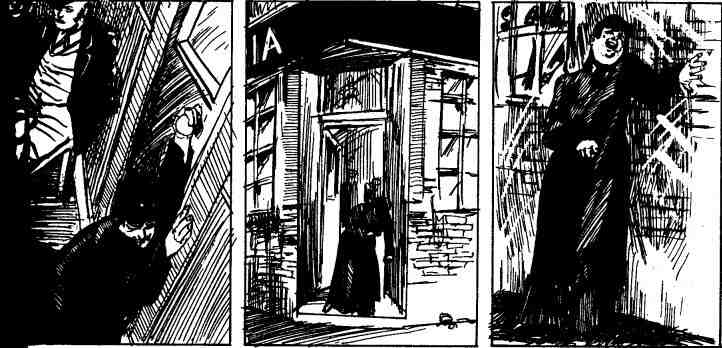

Campbell, a noted storyteller in his own right ( Bacchus, Alec),

lives up to Moore's highly demanding scripts,

portraying the dark immensity of London, from the hulking

cathedrals towering above the city, to the people running

through the streets.

This is the Ripper's story. From his early beginnings as a child,

curious to learn the inner workings of the cosmos;

to his professional rise, to become the Royal Physician;

to his vision-inducing heart-attack, and awakening to knowledge

of his Master; and to his final quest to further exalt that Lord.

Not quite the malefic slasher of stage and screen, but a

logical, intensely faithful man, carrying out what he believes

to be his self-appointed mission for God.

But it is also London's tale, a tale of the city of that time

and her people. Of the horror that existence holds for the people

of that city, of several simple, callous, unthinking cruelties,

that slap you in the face for their very unexpectedness.

Despite the grander themes shaping the flow of the story,

we are never allowed to forget the basic humanity of

these miserable players on the stage

There is no character in this tale so depraved, so brutalized, but that

Moore and Campbell make them touch our hearts, see some small spark

of humanity that we might empathize with. And thus further feel the

horror of their tale.

The People (and London's architecture)

Moore and Campbell's characters are living, breathing people,

bringing the London of 1888 to vivid life in our heads.

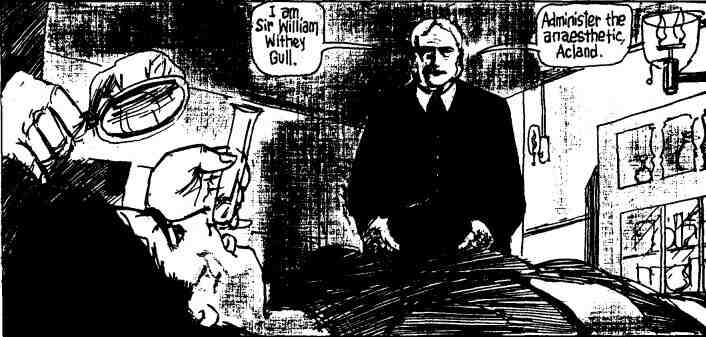

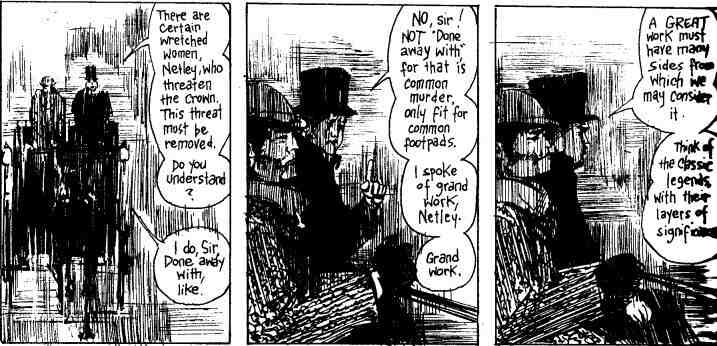

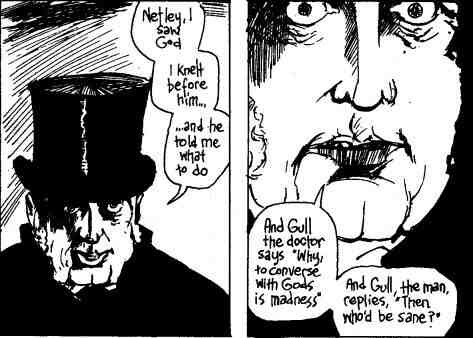

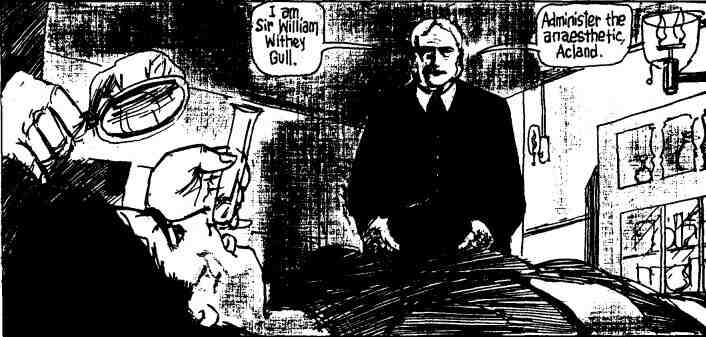

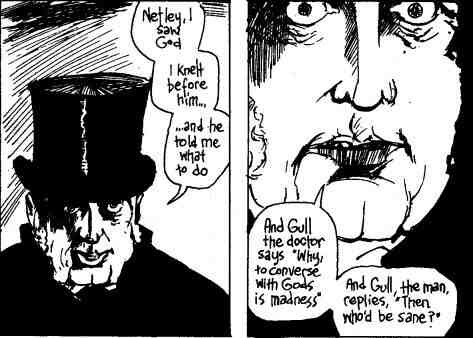

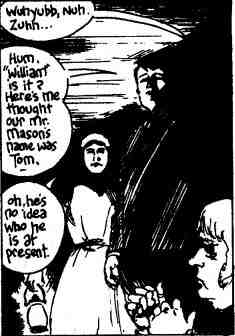

Sir William Withey Gull is a fanatic, a man so lost in his

own terrible vision, that he is willing to do whatever it

takes to achieve it, twisting his associates' arms, preying

on the fears of his superiors, using his own unshakable will

to forge through all obstacles like a juggernaut. A stern

man, raised to hold Duty above all, but his devotion to that

Duty swathes him in rapture.

Gull, alone, of all the characters here, rises above the demands

of the earth that he is rooted in, to seek out a higher, spiritual

plane. He maintains an ethereal attitude, striving to complete his

self-appointed task despite the frailty of his human tools, the

other players on this stage are very firmly rooted in their earth.

|

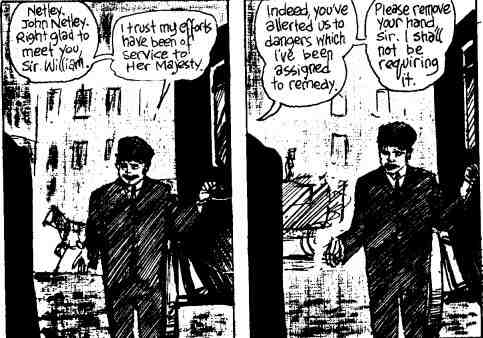

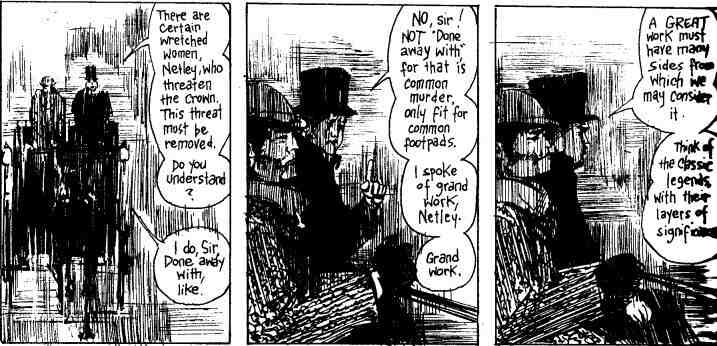

Moore takes a particular delight in parallels and

double entendres, running through all his writing,

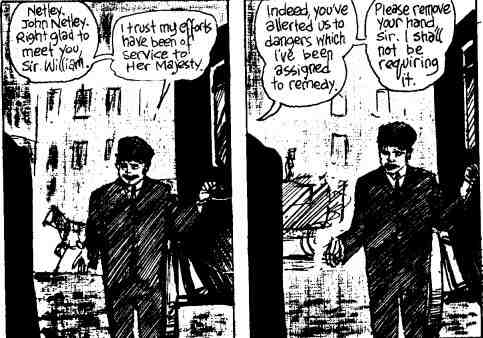

In another of these, Gull is paired with Netley,

an ignorant and unthinking man of the streets,

a person conscious of nothing more than his

desire to get ahead in life, a man very much of the earth,

seeking higher knowledge only to aid him in this world.

Netley's shallowness, ingratiatingly servile nature and

alarming stupidity make him the perfect unthinking tool for Gull

to use.

|

|

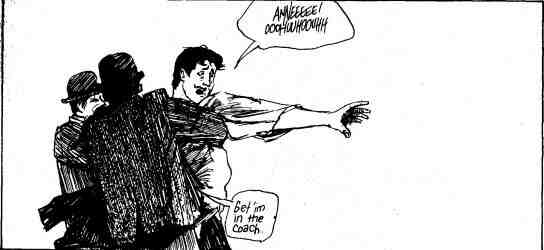

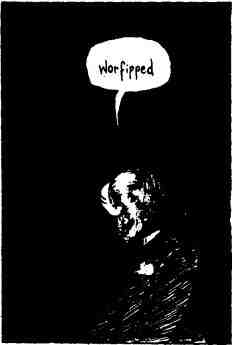

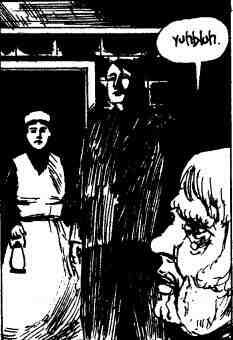

Netley is a little man, all too conscious of it, and seeking

power and advancement; yet, when he realizes the nature of the

immense maelstrom he has gotten himself into, he panics, collapses.

It's not the idea of murder that bother Netley; life itself is cheap

in London of the time. No, it's the consciousness of being totally

overwhelmed, enveloped by an all-encompassing power that is now

an inextricable part of his daily life; it's Gull's staggering revelation

that he always has been surrounded by this grand magic.

Awakening produces terror here, rather than the grand enlightenment

and vision provided to Gull. (Chapter 4 pages 36-37)

|

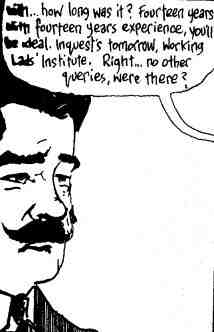

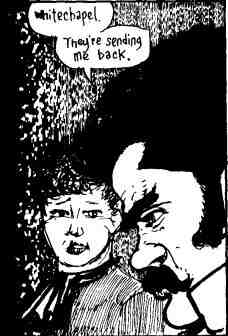

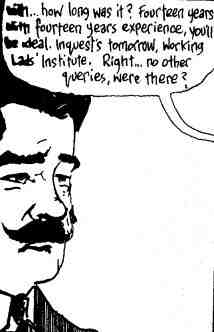

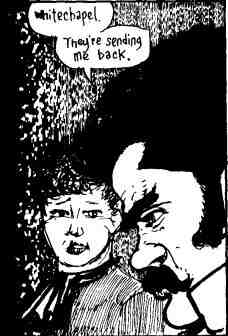

Inspector Abberline is a man thrown back into a brutalized,

decomposing part of London that he loathes, but is forced

back into, out of political necessity.

|

|

|

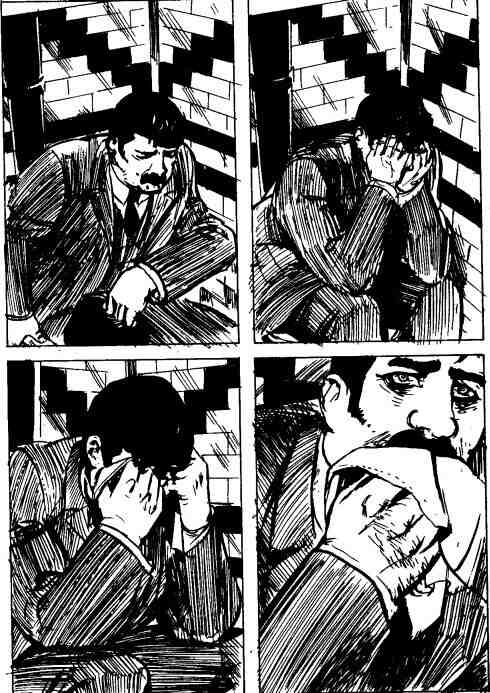

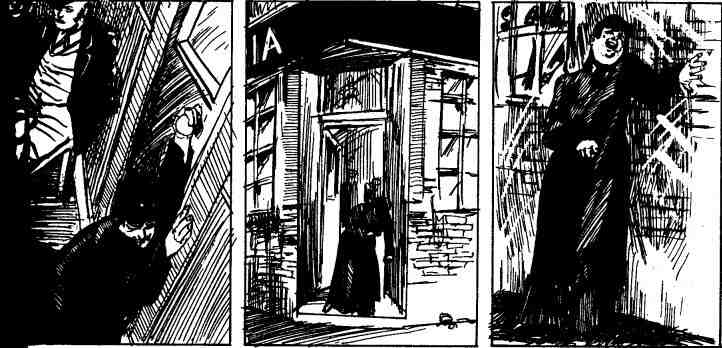

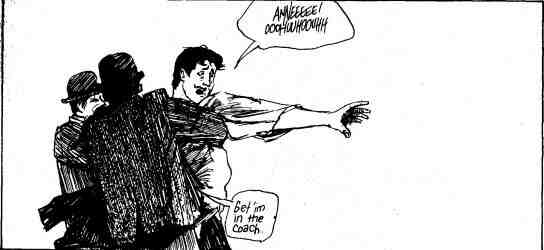

Notice Campbell's depiction of the explosive frustration on Abberline's

face, as he is transferred back to Whitechapel, the seat of his contempt;

and contrast this to the disgust on his face when he realizes the true

game being played within the corridors of power that he had

coveted (Chapter 13 pages 8-11)

There's more than a small part of Abberline which empathizes

with the denizens of Whitechapel; very much a man of the soil,

it had been his home for fourteen years, and he knows it better

than he understands the new realm of privilege that he has been

drawn into.

|

|

|

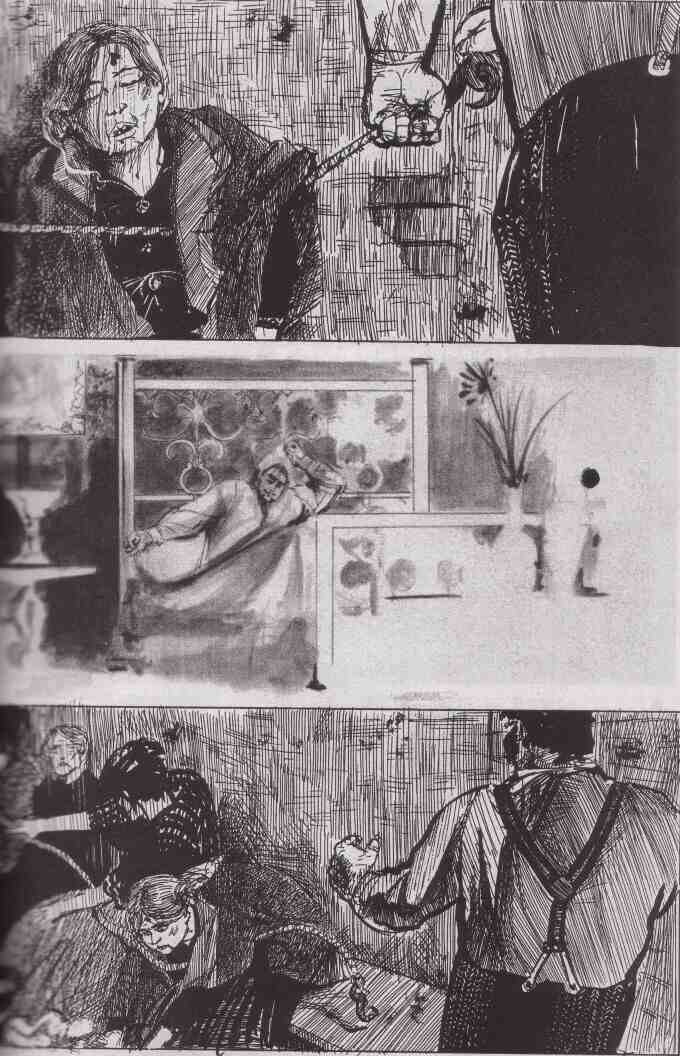

The prostitutes, Gull's targets, are perpetual victims,

desperately trying to stay alive in a London that makes

even day-to-day living difficult.

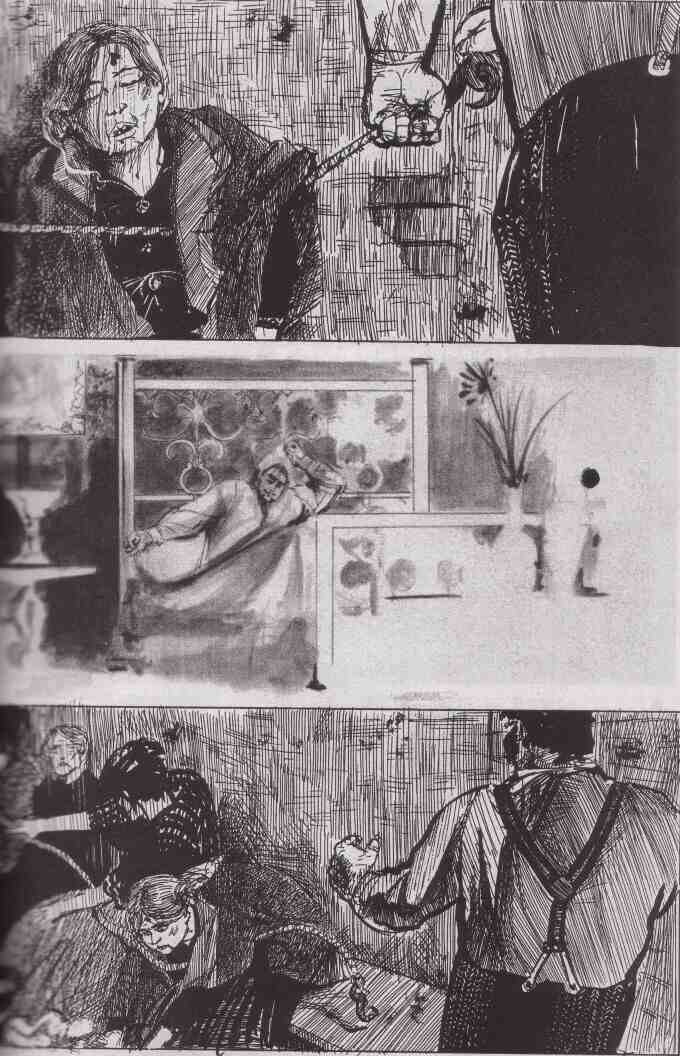

Look at Campbell's Chapter 5, where he visually contrasts

the two Londons, Gull's London of privilege, and the

hellish London of the poor. Soft grays ease Gull into his

daily routine, while sharp cold blacks topple the women

out of their peaceful sleep into London's cold.

The Ripper's victims are not particularly lovely women,

and cannot said to be leading a happy life by any means.

Observe the stark, hopeless terror of the prostitutes, faced

with death or worse at the hands of the London mob (Chapter 3)

And yet Campbell never fails to sink in a needle to remind us

of their humanity, time and again; Mary Kelly's calm, quiet

smirk (Chapter 3, page 14) or the piteous misery of Annie

Chapman (Chapter 7 page 5); or Kate Fellowes snatching

a few moments of joy, in the midst of her drudgery (Chapter 9)

it becomes impossible not

to feel their torment, the sad, heart-rending despair, of a person

condemned to this Hell through no fault of their own, and now

unable to even conceive of an escape from it.

|

|

London is no less a character in this tale, enveloping

and shrouding the characters, driving them down its chosen path.

|

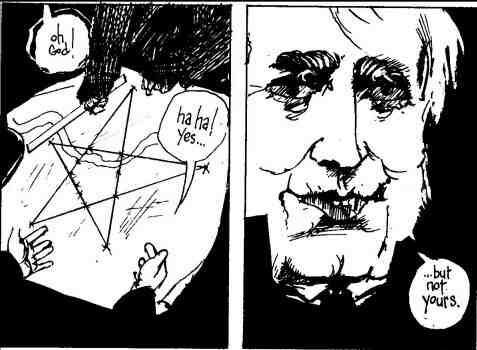

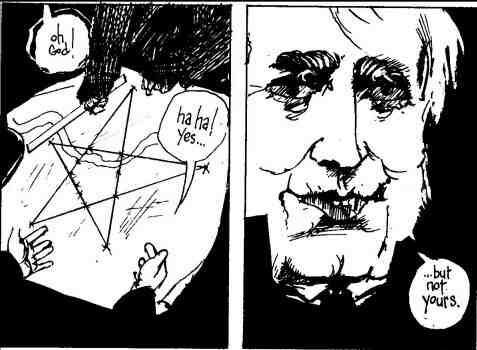

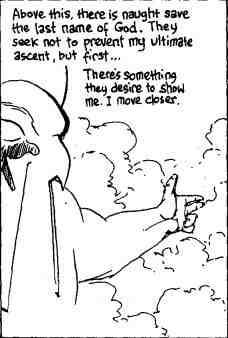

In the astonishingly powerful Chapter 4, we first see the

grand plan drawn out by Gull, and the forces surrounding him

that he capitalizes on to fulfil his task.

Here, we see Gull's chilling revelation of his ultimate goal, made

even more terrifying by the look of complete satisfaction on his face

Gull's studies through Masonry have revealed to him the grand

plan behind London's construction;

the menacing constructions not only exalting the Deity but

also stripping away the humanity from the little man;

not bringing the man up to the level of the Deity, but

rather stressing the difference between them, making man

far more acutely aware of how very little a thing he is.

Every little detail, from the grand to the mundane, from

the overpowering dome of St. Paul's, to the simple horse-brasses

mounted on every carriage in London, bears witness to

the grand magic mounted in this city.

|

|

The city, an immense occult engine, prepared by occult architects

and Masons through the ages, is now primed and targeted, prepared

by a kill, and aimed at her Queen's foes by a fanatic willing to

do anything for his Liege, and more, if it also serves his

Deity. (Actually, serving his Liege is only incidental to Gull's

higher plan, "the very tip of the iceberg". Victoria does not

suspect what she has unleashed, in her attempts to protect her

family's reputation.)

As Hawksmoor built up the colossal London above,

so too does Gull now build up his task in the streets below.

London's innocents are expendable pawns in a plan to extoll

the Gods, and thereby complete Gull's mission on Earth.

Magnifying and focussing London's darkness ...

For London is Hell ...

Strangely, the protagonist does not seem to cause as much agony

and despair as the environment itself. Whitechapel, a Hellish

nightmare to its poorest inhabitants, produces far more misery

to its people than Gull. Campbell does more than justice to

Moore's script, in producing an image of a Pit, its frightened

inhabitants preying on each other, resigned to their fate,

perpetually yearning for a better existence but without any

real hope of one, desperately snatching at whatever small

morsels of joy they can extract from the darkness.

This London is a very Hell ... and there are no happy characters

here ... all of them suffering, in one way or another:

|

A Prince, bullied and controlled by his Imperial mother,

denied any chance of his own happiness;

|

|

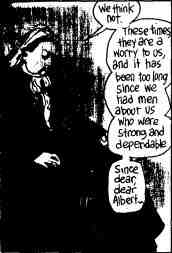

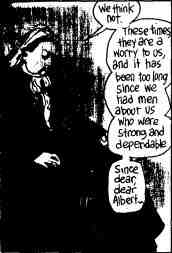

The Empress herself, fearing revolution, living a cold and

loveless existence;

|

|

|

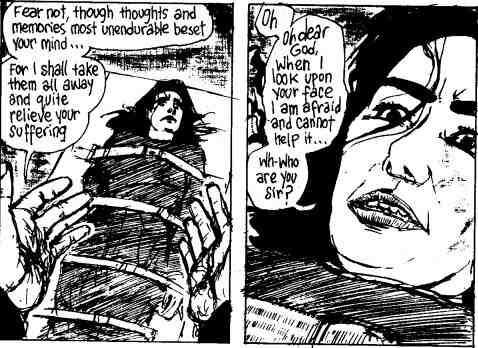

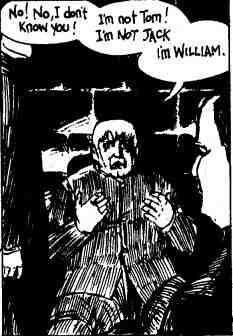

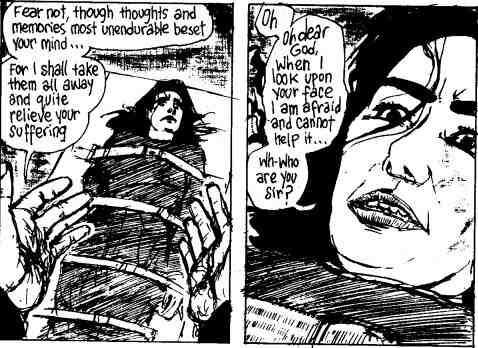

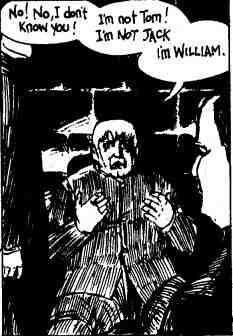

A shopgirl, robbed of her very mind, a pawn tossed about the

chessboard by forces beyond her control;

|

|

|

The prostitutes of London, cursed into an early life of despair,

with little hope of improvement;

|

|

|

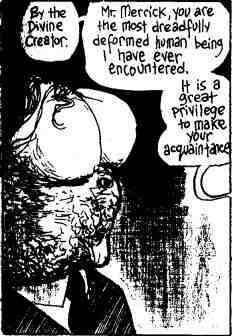

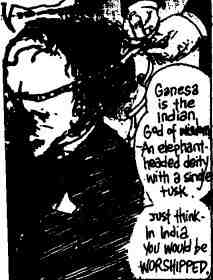

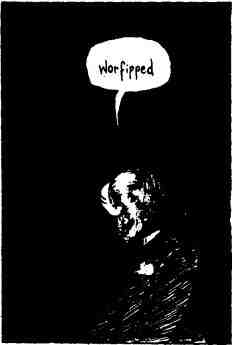

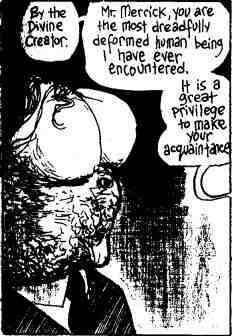

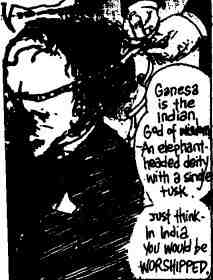

The Elephant Man, condemned to the Hell of his own body,

but dreaming of the Heaven revealed to him by Gull;

|

Gull, himself, escaping a mortal Hell by an attempt to

seize Heaven

|

|

The closest any of these characters ever come to Heaven is

through their interactions with Gull; his casual words

presenting the vision of a better world to John Merrick;

and the few moments of childlike joy we see on the face of

Polly Nicholls, a young woman robbed of her childhood, are those

given to her by Gull, just prior to her death at his hands;

a final contact with Gull's luminous Heaven, just before she

passes out of the Hell that her life had become.

We are all of us in the gutter, but some of us are

looking at the stars." - Oscar Wilde

In Moore's book, the only person who is looking at the stars

is Gull himself. All the others are so lost in the pain of the

gutters of Whitechapel that they see nothing beyond; no hope left.

An occasional desperate dream of escape is all that's left to

them, followed by the inevitable and quick dash of reality,

and a return to their hopeless lives. Gull alone sees the

glory of his task, permeating all the world.

Finale

|

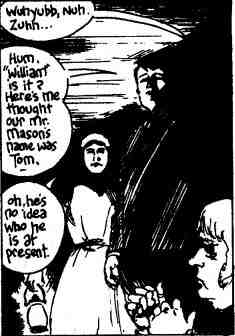

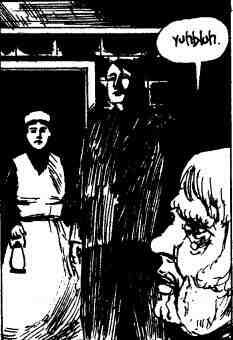

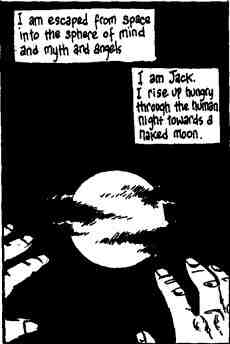

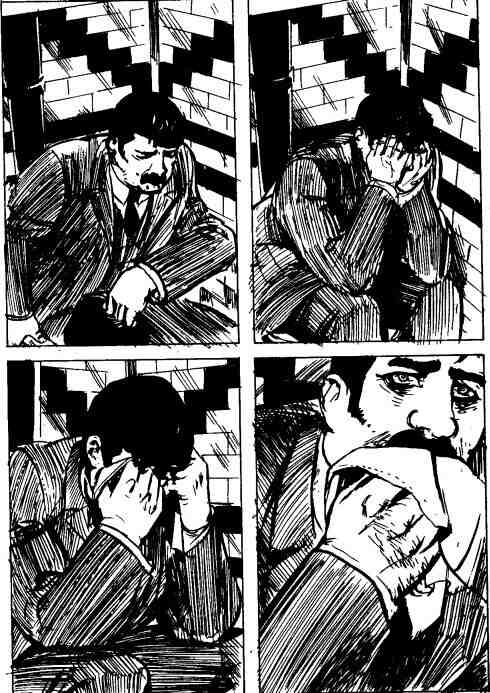

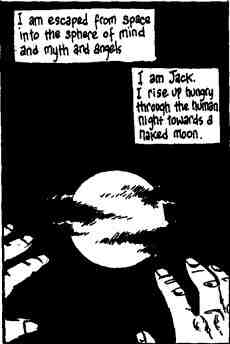

In another of Moore's mirrors, note Chapter 14, where

Gull simultaneously plumbs the depths of madness,

as he rises towards his ultimate goal, far above the

common rut.

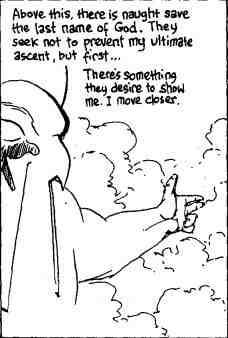

This is Gull's final triumph ... escaping from the earthy surroundings,

into the grander, larger design that surrounds him.

Then further, outside even the three dimensions, into the

larger fourth; and finally, into the face of God.

And the power of that ascension casts ripples through time,

as the strength of Gull's faith, the intensity of his belief,

affects others in his wake. The completion of his grand

achievement simultaneously hurls him into the heights

of his final goal as well as into the depths of madness.

He is swept up in the rapture that envelopes him, but

rapidly losing all connection with his earthly life

As he has made use of the structures built around him

over time, so too does he now create his own occult

structure, one extending through time, and spreading its

ripples down the years.

And the strength of his creation influences other minds

across the years, reflections and imitators, shadows of

the original Ripper, sympathetic minds walking the path

first traced by Gull;

the grand design arising in shallower circles (first a

century, then fifty years, then twenty-five and so on),

moving through time towards a convergence

And Gull's ascension completes, his mind reaching eternity,

finally escaping his earthen body.

|

|

Moore combines a skillful blend of research and fiction,

not resisting the appeal of including several coterminous

characters and vignettes (Crowley's presence in London,

Hitler's birth) to bolster his tale across time. The

detailed glossary of his research and annotations of his

work in writing this book gives still more insight into

the creative process behind it.

In the final appendix, Moore wryly makes note of the work

done by prior Ripperologists, observing their effect on

each other (including his own work).

He acknowledges the immense quantity of legend that has

built up around the Ripper, and the extremely muddy line

drawn between myth and reality (often crossing boundaries),

and his own contribution to those legends (further muddying

and blurring the waters).

This is easily one of the finest works in the medium,

and well deserves a place on any reader's bookshelf.

Richly detailed, the book rewards multiple reads with

new insights into the tale.

Review (c) Bala Menon , 2001

All images on this page (c) Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell,

and used under the Fair Use doctrine

FROM HELL (c) Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell, 1989, 1999