New York Times: August 22, 2003

PUBLIC LIVES

Man With a Mission: Saving Beauty, Saving Grace

By ROBIN FINN

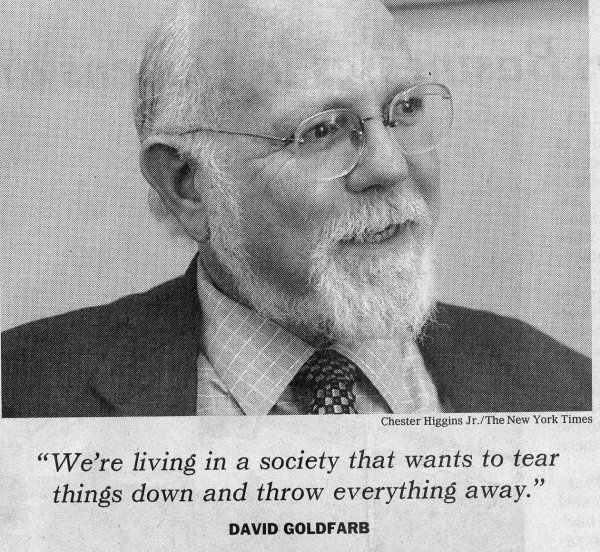

THINKING of paving paradise and putting up a parking lot? If paradise includes an edifice over the age of 75, you may catch an irritable earful, and possibly worse, from David Goldfarb, a white-bearded lawyer who, at 55, blithely confesses to looking older than chronology deems him. Which perhaps accounts for his identification with old-timers, whether human (his specialty is elder law) or architectural (his voluntary avocation is landmark preservation). And yes, he resorts to litigation if prodded; can't expect ramshackle bungalows and Victorians to defend themselves.

Bulldozers aren't typically the designated villain of urban rants, but they are for Mr. Goldfarb, new president of the Historic Districts Council, which helps city neighborhoods pursue landmark designation. "In some boroughs, the whole diversity of the city is being lost," he grouses. Tartly. "Everything is being turned into a town house."

This moves him to frustration, sometimes to lawsuits, and often to arguments with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, a city agency that is, he fears, doing the Big Apple equivalent of fiddling while Rome burns: instead of hustling to designate historic districts, he claims it too often empowers the bulldozer brigade. But there's more. The commission is, he says, not just slow to act, but covert about it.

"They meet in secret, their designation committee plays it close to the vest, and when they deny landmark status, like they did in Richmond Hill and with the Spanish Camp," he says, referring to proposed historic sites in Queens and on Staten Island. "They won't tell us why." He sinks into an office chair at 350 Fifth Avenue. For those whose grasp of landmarks is shaky, 350 Fifth doubles as the Empire State Building, tied with the Woolworth building as his favorite Manhattan structure. Mr. Goldfarb's firm, Goldfarb Abrandt Salzman & Kutzin L.L.P., moved in last year; he uses the "love" word to describe his feelings for it, gets a thrill every time he enters its Art Deco vestibule. Born in Brooklyn, he grew up amid deco in Miami and conjures a retro deco vibe every summer by putting a pair of flamingos in the backyard of his Staten Island Victorian.

But if Mr. Goldfarb thinks closed commission meetings are illegal, why not sue? He says he may. First, he's trying diplomacy in the form of a letter campaign. Then there's the latest insult, a proposed 50 percent escalation of building permit fees for properties with landmark designation: 21,000 individual properties in 80 neighborhoods are presently protected by — and answerable to — the city's landmarks law. Mr. Goldfarb sees the fee increase as a hardship, and a deterrent to new designations. Last month his group held a protest at City Hall.

"We're living in a society that wants to tear things down and throw everything away," laments Mr. Goldfarb. "Every day you see the bulldozers in Richmond Hill. Particularly when it comes to neighborhoods in the outer boroughs, the Landmarks Commission just doesn't get it. Take them to a row of brownstones in Brooklyn Heights and they say, `Yes, this is pristine and worth saving.' Take them to a bungalow colony on Staten Island and they say, `That's a shack.' "

The Edgar Allan Poe House in Greenwich Village, where a visit to the basement transported him deep into "The Cask of Amontillado"? Bulldozed to enable expansion by, irony of ironies, the source of Mr. Goldfarb's law degree, the New York University School of Law. The Judson House, Poe's neighbor? Smashed to smithereens for the same reason. He sued to stop it, but lost. "I didn't want to sue my own alma mater," he says, "but I couldn't find any other firm that would take the case."

The Dorothy Day Cottages and Spanish Camp on Staten Island, a site he prized for the singular glimpse it provided into a social movement of yesteryear? Leveled on behalf of an influx of soulless structures that Mr. Goldfarb refers to as McMansions. "It makes me sad," he says. "I'm not saying every bungalow colony has to be preserved, but we should be looking out for the ones that have social and historic significance."

Lately, Mr. Goldfarb hears the growl of the bulldozers right on his own block, where Victorian houses framed by low stone walls are being obliterated in favor of, yuck, town houses. Since 1973, he and his wife, Liz, have lived in a shingled 1890's Victorian, but their section of St. George has not been named a landmark; anything goes.

HE had brown hair to his shoulders as student body president at the University of Wisconsin in 1969, when the Madison campus was a war zone itself. After law school, he worked for Legal Aid for 15 years. He cut his hair, shaved his beard, wore a suit and tie: "You didn't want our clients to feel like they were getting less of an attorney than anyone else." Still does the suit thing; even frowns on dress-down-Fridays at his firm. He is, he says, accustomed to risking unpopularity. When Staten Island flirted with secession, he debated against it. He opposes the death penalty, no exceptions. He is not opposed to town houses and high-rises, just to bulldozing antiques to accommodate them. Spoken like a man who, when his beard grew back in white, preserved it.